"The civilized soldier when shot recognizes that he is wounded and knows that the sooner he is attended to the sooner he will recover. He lies down on his stretcher and is taken off the field to his ambulance, where he is dressed or bandaged. Your fanatical barbarian, similarly wounded, continues to rush on, spear or sword in hand; and before you have the time to represent to him that his conduct is in flagrant violation of the understanding relative to the proper course for the wounded man to follow—he may have cut off your head." --Sir John Ardagh, discussing the necessity of "dum dums" (or expanding bullets) for international warfare, at the Hague Convention of 1899, which subsequently banned their use for international conflicts. Via Wikipedia.

Tuesday, January 14, 2014

Monday, November 18, 2013

Reflections from Bouldering

I've been spending a lot of time bouldering recently, a few times a week. Besides strongly incentivizing me to lose 10 lbs, I have started to learn some interesting lessons, the hard way.

Indoor bouldering is like rock climbing, but the highest it gets is about 17 feet, the floors are padded about two feet thick, and there are no ropes. That means I can show up whenever I want, alone, and climb for as little or as much time as I want, and not need someone to belay me. It also means that the first few times you climb, it can be pretty unnerving because when you fall, you just fall, boom, onto the mat. In fact I noticed that as I grew more tired during climbing, if I thought I wasn't going to be able to make it to the top, I would frequently climb or jump down while I still had control, even if I had some power left, because I wanted to avoid being all the way at the top and having no strength left, forcing me to fall uncontrolled from the top, as opposed to falling in a controlled way from halfway up. But, after you fall from the top a few times, this turns out to be a mistake: falling from the top doesn't hurt. That's why they let you do it and don't get sued too often (although, the place is actually blanketed in cameras, in deference to our tort-happy society: just in case someone does something stupid and sues, they have you on record.)

But, the more interesting thing that I discovered was that the barrier to failure was often simply exhaustion rather than skill. And this has a particularly interesting consequence: often, the best next move is making the next move. As a beginner, your instinct is to stop at each hold, look around, and see where the next move is. Which hold can you reach without falling over? But, watching other skilled climbers in the gym, they do it differently: first, they study the route before they start climbing. Then, once they're on their way up, they move gracefully and smoothly from one hold to another, and importantly, they keep moving. While you're stopped, looking around, your arms are growing tired, your tendons are aching, the skin on your fingers is starting to grate under the hand holds. And what I found, through brutal trial and error, was that I was much more consistently successful if I just kept moving. In an indoor bouldering gym, the holds are laid out somewhat logically, but also somewhat deviously, so that it's not always obvious what the solution is. But your brain moves pretty quickly, and without even realizing you're doing it, you're not even considering 9 out of the next 12 possible moves. The extra 5 seconds that it takes per move to decide amongst those three remaining moves is probably the difference between near-complete exhaustion and complete exhaustion. And complete exhaustion means failure. I'm a big fan of stopping and thinking about what you're doing, but the lesson is, when you're resource constrained and time is not on your side, don't think too hard. You might back yourself into a corner, but it's no worse than falling on your ass.

Indoor bouldering is like rock climbing, but the highest it gets is about 17 feet, the floors are padded about two feet thick, and there are no ropes. That means I can show up whenever I want, alone, and climb for as little or as much time as I want, and not need someone to belay me. It also means that the first few times you climb, it can be pretty unnerving because when you fall, you just fall, boom, onto the mat. In fact I noticed that as I grew more tired during climbing, if I thought I wasn't going to be able to make it to the top, I would frequently climb or jump down while I still had control, even if I had some power left, because I wanted to avoid being all the way at the top and having no strength left, forcing me to fall uncontrolled from the top, as opposed to falling in a controlled way from halfway up. But, after you fall from the top a few times, this turns out to be a mistake: falling from the top doesn't hurt. That's why they let you do it and don't get sued too often (although, the place is actually blanketed in cameras, in deference to our tort-happy society: just in case someone does something stupid and sues, they have you on record.)

But, the more interesting thing that I discovered was that the barrier to failure was often simply exhaustion rather than skill. And this has a particularly interesting consequence: often, the best next move is making the next move. As a beginner, your instinct is to stop at each hold, look around, and see where the next move is. Which hold can you reach without falling over? But, watching other skilled climbers in the gym, they do it differently: first, they study the route before they start climbing. Then, once they're on their way up, they move gracefully and smoothly from one hold to another, and importantly, they keep moving. While you're stopped, looking around, your arms are growing tired, your tendons are aching, the skin on your fingers is starting to grate under the hand holds. And what I found, through brutal trial and error, was that I was much more consistently successful if I just kept moving. In an indoor bouldering gym, the holds are laid out somewhat logically, but also somewhat deviously, so that it's not always obvious what the solution is. But your brain moves pretty quickly, and without even realizing you're doing it, you're not even considering 9 out of the next 12 possible moves. The extra 5 seconds that it takes per move to decide amongst those three remaining moves is probably the difference between near-complete exhaustion and complete exhaustion. And complete exhaustion means failure. I'm a big fan of stopping and thinking about what you're doing, but the lesson is, when you're resource constrained and time is not on your side, don't think too hard. You might back yourself into a corner, but it's no worse than falling on your ass.

Friday, November 1, 2013

We Apologize for the Interruption in our Interrupted Programming

Not much call for blogging these days; most of the interesting Data Blogging Topics(tm) have been around the Snowden NSA leaks, and I've been trying to slog through a number of other things at work, so it's hard to find the energy to get invested in it. But, I wanted to stop by the blog and give you a brief update, to the assembled masses who may read this later (and, I have found out the hard way, blogs left unattended can come back and bite you in the ass.)

When the Snowden/NSA leaks first started coming out, the scope was pretty limited. Phone call metadata logging was the big topic, and my comments were primarily technical in nature. My decision to not express a particular opinion on the politics might have been construed as a tacit approval, or at least a lack of outrage, and I think the latter was probably not far off.

In the meantime, however, a lot more things have come out, such as the fact that the NSA has p0wnz0red the entire internet, and we've been eavesdropping on foreign heads of state and American citizens for essentially no reason. So, I wanted to update, for clarity, my feelings: this is odious, unamerican, and a fundamental breach of the public trust. The excellent New Yorker article about Alan Rusbridger, the editor of The Guardian, indicates that we're still just seeing the tip of the iceberg; the only limiting factor is how fast the journalists can process and understand the documents they've been given*. If you want to read more, the incomprable Bruce Schneier is your go to source, and I truly couldn't hope to add anything.

Sadly, in my search for hyperbole to compare this with, my mind goes back only as far as the buildup to the Iraq War, and it's hard for me to draw a comparison really: it's apples to oranges. The Iraq war was a breach of the public trust in a fundamental way, but it involved a lie which resulted in the deaths of over 100,000 humans. It's hard for me to draw a meaningful comparison there that doesn't minimize those deaths. But the consequences of fundamentally weakening the internet is hard to grasp, in both its scope and consequences. The ripples from this tidal wave will continue to leave marks in the sand well into the next generation, and only time will tell.

*The article refers also to Rusbridger's memoir in which he interleaves his Herculean work publishing the Snowden leaks with his year long struggle to master a particularly difficult work by Chopin. I immediately thought, "He must not have any children," but of course, we find out, he does. It is times like this that I am reminded of the late great David Foster Wallce's characterization of Wilhelm Leibniz in one of my favorite books ever written, "Everything And More: A Compact History of Infinity". He describes Leibniz, one of the inventors of the calculus, as "a lawyer/diplomat/courtier/philosopher for whom math was sort of an offshoot hobby", which he tags, in typical David Foster Wallace fashion, with a footnote, saying only, "Surely, we all hate people like this."

When the Snowden/NSA leaks first started coming out, the scope was pretty limited. Phone call metadata logging was the big topic, and my comments were primarily technical in nature. My decision to not express a particular opinion on the politics might have been construed as a tacit approval, or at least a lack of outrage, and I think the latter was probably not far off.

In the meantime, however, a lot more things have come out, such as the fact that the NSA has p0wnz0red the entire internet, and we've been eavesdropping on foreign heads of state and American citizens for essentially no reason. So, I wanted to update, for clarity, my feelings: this is odious, unamerican, and a fundamental breach of the public trust. The excellent New Yorker article about Alan Rusbridger, the editor of The Guardian, indicates that we're still just seeing the tip of the iceberg; the only limiting factor is how fast the journalists can process and understand the documents they've been given*. If you want to read more, the incomprable Bruce Schneier is your go to source, and I truly couldn't hope to add anything.

Sadly, in my search for hyperbole to compare this with, my mind goes back only as far as the buildup to the Iraq War, and it's hard for me to draw a comparison really: it's apples to oranges. The Iraq war was a breach of the public trust in a fundamental way, but it involved a lie which resulted in the deaths of over 100,000 humans. It's hard for me to draw a meaningful comparison there that doesn't minimize those deaths. But the consequences of fundamentally weakening the internet is hard to grasp, in both its scope and consequences. The ripples from this tidal wave will continue to leave marks in the sand well into the next generation, and only time will tell.

*The article refers also to Rusbridger's memoir in which he interleaves his Herculean work publishing the Snowden leaks with his year long struggle to master a particularly difficult work by Chopin. I immediately thought, "He must not have any children," but of course, we find out, he does. It is times like this that I am reminded of the late great David Foster Wallce's characterization of Wilhelm Leibniz in one of my favorite books ever written, "Everything And More: A Compact History of Infinity". He describes Leibniz, one of the inventors of the calculus, as "a lawyer/diplomat/courtier/philosopher for whom math was sort of an offshoot hobby", which he tags, in typical David Foster Wallace fashion, with a footnote, saying only, "Surely, we all hate people like this."

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Less Talky, More Hacky

Light posting lately. I'm spending my time learning MongoDB, CouchDB, jQuery, Bootstrap, and node.js, in pursuit of various projects. Gotta get hip with the web technologies, dontchaknow.

I was an invited speaker at Sibos last week in Dubai, and spoke on money laundering and counter-fraud in commercial banking, and specifically how the same types of data comes up over and over again, so it doesn't make sense to field a different platform for each problem. My talk was apparently well received.

I was an invited speaker at Sibos last week in Dubai, and spoke on money laundering and counter-fraud in commercial banking, and specifically how the same types of data comes up over and over again, so it doesn't make sense to field a different platform for each problem. My talk was apparently well received.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Theory Thursday: The Central Limit Theorem

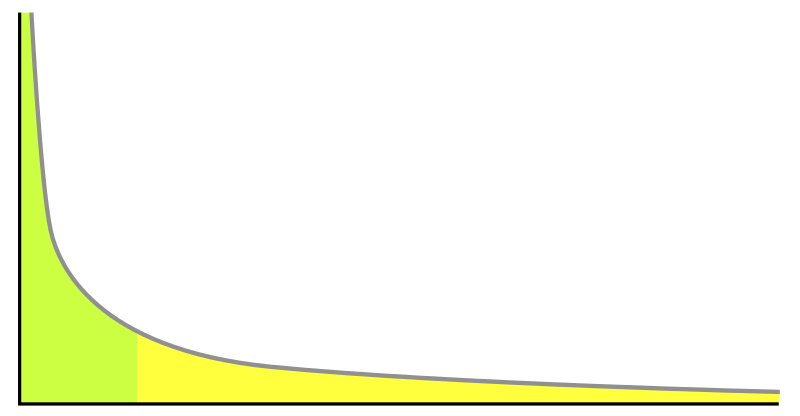

Back when I was employed researching the mysteries of the universe by pipetting lots of stuff, I used to say that physics was the study of things that are pointy in the middle and small on the ends, so that we can ignore the ends. Essentially, the idea in much of science is to figure out how to boil a phenomenon down to a few variables that have reasonably well defined values, i.e., a mean or average value. All measured variables have a distribution, but not all distributions are pointy in the middle, and only for distributions that are pointy in the middle does it make sense to calculate the average value. As a classic counterexample, the power-law distribution doesn't have a pointy middle:

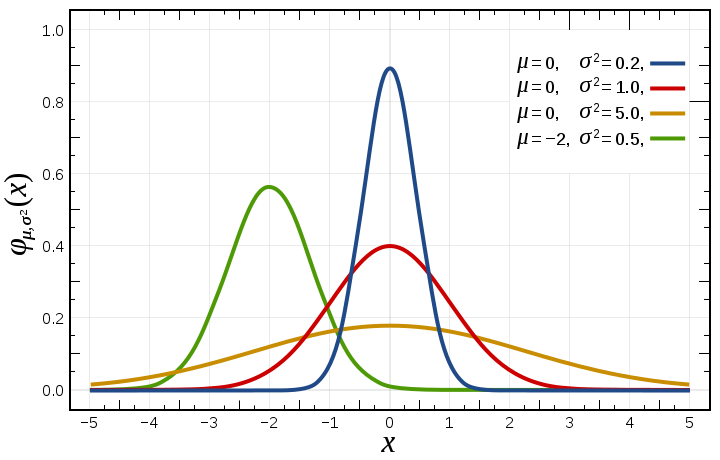

You can still, of course, calculate the mean value of this distribution by summing over all the values and dividing by the number of values. But the point is that it won't mean much intuitively: "most" of the values won't be "around" the mean value. They're all over the place. So, if we want to be able to talk about measuring a "variable", we'd like it to have a peak in the middle. In particular, it would be really handy if our distribution was a Normal Distribution (aka, the famous Bell Curve, or Gaussian, after the legendary mathematician and physicist Carl Freidrich Gauss.)

A normal distribution has a couple of very nice properties that make math a lot easier:

Luckily for us, the Central Limit Theorem has our back. What it says, basically, is that if you take a whole bunch of random variables, what you get out will probably* be pretty close to a normal distribution. And this is good news for people who like things high in the middle and flat on both ends**. Most real processes in the world are the result of a bunch of sub-processes, each of which has its own distribution. For instance, the average number of fish in a lake may depend on the average rainfall, the average temperature, the average number of fisherman, and the average amount of food, each of which in turn is affected by a number of other variables. When we mush these all together, things tend towards a normal distribution, which lets us deal with most natural processes in a tractable way mathematically, giving us a universe in which many things of interest have well defined average values, because they're peak-y.

*Without getting too deep in the weeds, this is true assuming your distributions have both a finite mean and a finite variance. Some power-law distributions do not have a finite variance, because they have what's called a "fat tail": basically, they don't converge to zero fast enough, so there's lots of stuff way out towards infinity. If all your variables are like this, you're in trouble. Luckily for us, the real world is mostly composed of things that have finite variance.

**As opposed to Ohio, which is high in the middle and round on both ends.

You can still, of course, calculate the mean value of this distribution by summing over all the values and dividing by the number of values. But the point is that it won't mean much intuitively: "most" of the values won't be "around" the mean value. They're all over the place. So, if we want to be able to talk about measuring a "variable", we'd like it to have a peak in the middle. In particular, it would be really handy if our distribution was a Normal Distribution (aka, the famous Bell Curve, or Gaussian, after the legendary mathematician and physicist Carl Freidrich Gauss.)

A normal distribution has a couple of very nice properties that make math a lot easier:

- The mean, median, and mode are all the same.

- It's mathematically tractable to work with and has a simple form.

Luckily for us, the Central Limit Theorem has our back. What it says, basically, is that if you take a whole bunch of random variables, what you get out will probably* be pretty close to a normal distribution. And this is good news for people who like things high in the middle and flat on both ends**. Most real processes in the world are the result of a bunch of sub-processes, each of which has its own distribution. For instance, the average number of fish in a lake may depend on the average rainfall, the average temperature, the average number of fisherman, and the average amount of food, each of which in turn is affected by a number of other variables. When we mush these all together, things tend towards a normal distribution, which lets us deal with most natural processes in a tractable way mathematically, giving us a universe in which many things of interest have well defined average values, because they're peak-y.

*Without getting too deep in the weeds, this is true assuming your distributions have both a finite mean and a finite variance. Some power-law distributions do not have a finite variance, because they have what's called a "fat tail": basically, they don't converge to zero fast enough, so there's lots of stuff way out towards infinity. If all your variables are like this, you're in trouble. Luckily for us, the real world is mostly composed of things that have finite variance.

**As opposed to Ohio, which is high in the middle and round on both ends.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

Fingerprint Scanners and Network Privacy Effects

Yesterday, I had some snark for the assertion that Apple using biometric identification in a consumer product amounted to then taking your fingerprints "against your will". I also considered the ethical aspects of whether your neighbor's privacy choices affect yours. But from a technical perspective, I find myself still very interested in Jacob Appelbaum's assertion that this will have an impact on overall privacy (or, specifically, his privacy) via "network effects," and found myself thinking through what this might mean. What follows is a probably overly pedantic analysis of the idea of privacy network effects in general.

First, let's define what a "network effect" is in this context: technically, network effects of technology are ways in which the adoption of a technology by someone else makes that technology more or less valuable for me. As an example of a positive network effect, e-mail is more valuable if more people use it, because I can reach more people using e-mail. An example of a negative network effect is traffic or network congestion: the more people who use cars, the more traffic I have to contend with. I think, technically, we would construe a network effect on privacy for the iPhone fingerprint scanner to be one in which adoption of the device by others reduces @ioerror's privacy if he uses the same device. However, I think we can safely conclude that @ioerror won't be using an iPhone 5S, or if he does, he'll use a sharpie to disable the fingerprint scanner. So, more broadly construed, we might consider network effects in which other peoples' adoption of the iPhone 5S reduces @ioerror's privacy, or even more generally, reduces the privacy of other people who don't use the phone in general.

It's important to distinguish this from simple consumer choice: there may be an overall reduction in privacy because of peoples' choice to use the iPhone 5S fingerprint scanner, but they may make that choice entirely based on considerations of convenience. This is an important distinction because, in the absence of network effects, it means that there's effectively no moral angle to the fingerprint scanner: the very fact that a large market exists for such devices means that community standards accept such choices as valid*.

There are a few mechanisms by which we can imagine privacy network effects being propagated. I think it's clear from context that the case that @ioerror is worried about is the normalization of biometric identification: including fingerprint scanners in phones which lots of people use will make people less more complacent about fingerprint scanners in general. Is there evidence for this? There are certainly a lot of cases of the public accepting lower privacy standards for specific purposes. For instance, when TSA imposed full-body scanning at airports, a lot of people shrugged and walked through the scanners. But, there was no obviously identifiable network effect: we didn't start to see full-body scanners replace metal detectors at federal buildings or schools (although it may be too soon to tell.) It may be the case that there are downstream effects: have we seen a profusion of metal detectors in public places (ball games, emergency rooms, schools) in general? Probably; I can't find statistics on this, but casual observation strongly suggests it. Is there a case to be made that this is due to normalization of security technology into our everyday lives? Again, very possibly. But is that due to a network effect, or due to simply government policy and heightened media attention? That is much harder to establish.

Perhaps a more compelling example is the profusion of sites that now let you log in using your Facebook ID instead of tracking logins on their own. As such logins become more common, it's easier to shrug at the (very real) privacy considerations of linking your Facebook account to each additional site. An important difference between these two cases is cost: metal detectors and full body scanners are expensive. Software is cheap. Which leads us to a second potential mechanism for network effects: By including such devices in their mass produced phones, Apple will effectively bring the cost of such devices down to the point where other phone manufacturers may start using them, and it may come to the point where it is difficult to buy a smart phone without one. This, I think, is a much more easily demonstrated mechanism of network effect. However, both are highly indirect: the adoption of the technology by party A does not directly impact party B's privacy: it's only through a very indirect set of policy, economic, and attitude changes that such effects could be propagated, and it's far from clear that these effects are even close in magnitude to the simple market demand for such devices.

Then, of course, it bears questioning: how would fingerprint scanners actually impact our privacy? First, there's what I call The Strong Hypothesis:

The Strong Hypothesis is that the NSA will gather fingerprints en masse from iPhones and other devices, then use them to create a national database. Six months ago I would have rated this tinfoil-hat-silly. But, of course, the revelations of the last few weeks make a lot of us look pretty silly for thinking that way, so it's no longer possible to simply disregard that possibility out of hand.

The Weak Hypothesis is that, for instance, the FBI will be able to subpoena your fingerprints from Apple in order to compare them against fingerprints they've collected, when previously they would have had no way of getting your fingerprints short of hauling you in. Whether or not this could happen depends a lot on how the technology is managed, and it seems more likely than not that Apple will store the fingerprint data on the device in a way that precludes remote access. But Apple has done stupider things before, and trusting their commitment to privacy is probably not a good strategy.

So, to close the loop, a network-effects-privacy-impact might look something like this: Apple's introduction of the fingerprint reader to the iPhone 5S lowers cost and social barriers to similar devices, and we start seeing fingerprint scanners not just on phones, but on laptops, cars, at the airport, and even at the gym. Oh, wait...

*The same argument doesn't necessarily hold for things like cigarettes though: sale and consumption of cigarettes imposes externalities on people who don't consume them, in the form of second-hand smoke, and increased public healthcare costs. Even if the sale of cigarettes is evidence that the community approves of cigarette consumption in and of itself, the effects on others have highly complicating moral effects. This is why it's important to establish whether there are network effects in deciding whether there's a moral aspect.

First, let's define what a "network effect" is in this context: technically, network effects of technology are ways in which the adoption of a technology by someone else makes that technology more or less valuable for me. As an example of a positive network effect, e-mail is more valuable if more people use it, because I can reach more people using e-mail. An example of a negative network effect is traffic or network congestion: the more people who use cars, the more traffic I have to contend with. I think, technically, we would construe a network effect on privacy for the iPhone fingerprint scanner to be one in which adoption of the device by others reduces @ioerror's privacy if he uses the same device. However, I think we can safely conclude that @ioerror won't be using an iPhone 5S, or if he does, he'll use a sharpie to disable the fingerprint scanner. So, more broadly construed, we might consider network effects in which other peoples' adoption of the iPhone 5S reduces @ioerror's privacy, or even more generally, reduces the privacy of other people who don't use the phone in general.

It's important to distinguish this from simple consumer choice: there may be an overall reduction in privacy because of peoples' choice to use the iPhone 5S fingerprint scanner, but they may make that choice entirely based on considerations of convenience. This is an important distinction because, in the absence of network effects, it means that there's effectively no moral angle to the fingerprint scanner: the very fact that a large market exists for such devices means that community standards accept such choices as valid*.

There are a few mechanisms by which we can imagine privacy network effects being propagated. I think it's clear from context that the case that @ioerror is worried about is the normalization of biometric identification: including fingerprint scanners in phones which lots of people use will make people less more complacent about fingerprint scanners in general. Is there evidence for this? There are certainly a lot of cases of the public accepting lower privacy standards for specific purposes. For instance, when TSA imposed full-body scanning at airports, a lot of people shrugged and walked through the scanners. But, there was no obviously identifiable network effect: we didn't start to see full-body scanners replace metal detectors at federal buildings or schools (although it may be too soon to tell.) It may be the case that there are downstream effects: have we seen a profusion of metal detectors in public places (ball games, emergency rooms, schools) in general? Probably; I can't find statistics on this, but casual observation strongly suggests it. Is there a case to be made that this is due to normalization of security technology into our everyday lives? Again, very possibly. But is that due to a network effect, or due to simply government policy and heightened media attention? That is much harder to establish.

Perhaps a more compelling example is the profusion of sites that now let you log in using your Facebook ID instead of tracking logins on their own. As such logins become more common, it's easier to shrug at the (very real) privacy considerations of linking your Facebook account to each additional site. An important difference between these two cases is cost: metal detectors and full body scanners are expensive. Software is cheap. Which leads us to a second potential mechanism for network effects: By including such devices in their mass produced phones, Apple will effectively bring the cost of such devices down to the point where other phone manufacturers may start using them, and it may come to the point where it is difficult to buy a smart phone without one. This, I think, is a much more easily demonstrated mechanism of network effect. However, both are highly indirect: the adoption of the technology by party A does not directly impact party B's privacy: it's only through a very indirect set of policy, economic, and attitude changes that such effects could be propagated, and it's far from clear that these effects are even close in magnitude to the simple market demand for such devices.

Then, of course, it bears questioning: how would fingerprint scanners actually impact our privacy? First, there's what I call The Strong Hypothesis:

I've updated the iPhone fingerprint scanner diagram with an important detail Apple left out. pic.twitter.com/k63flx8y6j

— Dylan Tweney (@dylan20) September 10, 2013

The Strong Hypothesis is that the NSA will gather fingerprints en masse from iPhones and other devices, then use them to create a national database. Six months ago I would have rated this tinfoil-hat-silly. But, of course, the revelations of the last few weeks make a lot of us look pretty silly for thinking that way, so it's no longer possible to simply disregard that possibility out of hand.

The Weak Hypothesis is that, for instance, the FBI will be able to subpoena your fingerprints from Apple in order to compare them against fingerprints they've collected, when previously they would have had no way of getting your fingerprints short of hauling you in. Whether or not this could happen depends a lot on how the technology is managed, and it seems more likely than not that Apple will store the fingerprint data on the device in a way that precludes remote access. But Apple has done stupider things before, and trusting their commitment to privacy is probably not a good strategy.

So, to close the loop, a network-effects-privacy-impact might look something like this: Apple's introduction of the fingerprint reader to the iPhone 5S lowers cost and social barriers to similar devices, and we start seeing fingerprint scanners not just on phones, but on laptops, cars, at the airport, and even at the gym. Oh, wait...

*The same argument doesn't necessarily hold for things like cigarettes though: sale and consumption of cigarettes imposes externalities on people who don't consume them, in the form of second-hand smoke, and increased public healthcare costs. Even if the sale of cigarettes is evidence that the community approves of cigarette consumption in and of itself, the effects on others have highly complicating moral effects. This is why it's important to establish whether there are network effects in deciding whether there's a moral aspect.

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Fingerprint Panic!

So, it sounds like the shiniest new iPhone will have a fingerprint scanner for security. Bruce Schneier, naturally, has some interesting and relevant technical considerations which he voices, in particular, about what happens if Apple decides to store fingerprint data in the cloud. But it seems like there should be a secure way to do this: nobody is realistically going to actually store an image of the fingerprint, not even on the phone itself. Instead, they'll store a hash of some set of metrics derived from the fingerprint. If you add salt to the hash, and the salt is stored on the phone, then you still need an unlocked physical device for the hash to be useful at all; the cloud-stored version is useless, just like a salted password file.

On the other end of the spectrum, there's this:

Allow me to suggest, for the paranoid, a few practical steps to be taken here to foil The Man:

On the other end of the spectrum, there's this:

Allow me to suggest, for the paranoid, a few practical steps to be taken here to foil The Man:

- Don't buy an iPhone. Problem solved.

- If you absolutely must play Angry Birds, turn off the fingerprint reader and use a passcode. Better yet, use a non-numeric passcode.

- If you don't believe that turning off the fingerprint scanner will foil the NSA's backdoor into your phone, try using a Sharpie to color over the fingerprint scanner window.

With respect to the network effects: what do you care if someone chooses convenience over privacy? People do it all the time, with their Safeway club card, their credit card, their choice to go through the scanner instead of get a pat-down at the airport, etc. Privacy is a very personal decision. Some people crave it, and it's their constitutional right which I support staunchly. But lamenting the "network" or "societal" effects of other people choosing security, convenience, fame, or money over privacy makes you little different than a church pastor denouncing the gay lifestyle because of the effect it will have on children. Society as a whole is constantly making decisions about their personal trade offs of privacy versus convenience, and you can always go Galt and peace out to a cabin in the woods if the unwashed masses refuse to hear your speech. You might want to give up tweeting if you go that route though: you give up far more privacy in practical terms through Twitter, Google, and Facebook than you would from a fingerprint scanner on your phone.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)